Types of Kitchen Knives: Complete Guide to Choosing, Using, and Caring for Cooking Blades

Hi there — it’s Chef Marcus speaking.

Welcome to the part of the kitchen drawer that matters more than most people realize.

If you’ve ever held a knife and hesitated — not because it was dangerous, but because you weren’t quite sure which one to grab — you’re in the right place. This isn’t a listicle about “top ten knives every chef needs” (nobody needs ten). And it’s not a catalog rundown of steel types and handle shapes with no real-world context.

This is about the tools that live between your hands and your ingredients — the ones that turn raw, uncut chaos into something you can eat, serve, and take pride in.

- Foreword: Why Knives Matter

- Understanding Knife Basics

- Core Knife Types (And Why You Actually Need Them)

- Knife Sets vs. Buying Individual Blades

- Care, Storage, and Maintenance

- How It Feels in the Hand: Balance, Weight, and Fit

- Choosing Your First Real Knife: A Field Guide

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Closing: The Knife You’ll Actually Use

Foreword: Why Knives Matter

The first time I cared about a kitchen knife, I was trying to cut a tomato with a butter knife. I was about ten. My grandmother told me to help with the salad, and in my innocent determination, I grabbed the wrong blade — and promptly turned that tomato into a pulpy crime scene.

She didn’t scold me. She just handed me her knife. It wasn’t fancy. The blade was old, worn thin from decades of sharpening. The handle had burn marks near the rivets. But when I pressed it into the next tomato, it slid through like a whisper. Clean, confident, quiet. That was the moment it clicked: it wasn’t me doing the cutting. The knife was doing it. I was just steering.

Since then, I’ve come to believe that good knives don’t just make food prep easier — they change how you think about cooking. A well-balanced blade doesn’t fight you. It teaches you. It makes you slow down when you need to be precise and speeds you up when you’re in flow. It becomes part of your rhythm, like the way your wrist turns when you stir, or how your foot taps when you taste and hum at the stove.

And the truth is, you don’t need a hundred of them. You need a few that do what they’re supposed to do — and that fit your hand like they belong there.

This guide isn’t here to convince you to buy anything. It’s here to walk you through what’s actually out there, what each knife does best, how it feels when it’s doing its job right, and what to look for if you want a blade that’ll last more than a season.

We’ll get into steel types. Shapes. The weirdly specific stuff (like why bread knives are secretly amazing for way more than bread). But before we do, just know this: the goal isn’t perfection — it’s connection. Between you, your food, and the thing that makes contact first.

Let’s dig into the world of kitchen knives — not as collectors or gearheads, but as people who cook. Every day. For ourselves, our families, or just for the calm that comes from slicing something clean.

Understanding Knife Basics

Before we start naming names, let’s talk about what a knife actually is — and why the boring stuff (like edge grind and steel type) matters more than you’d think.

When most people say “knife,” they’re thinking of a blade and a handle. Fair enough. But the difference between a tool you trust and one that leaves your onions in shreds comes down to small things — how it’s built, what it’s made of, how it’s shaped, and how all those parts talk to each other.

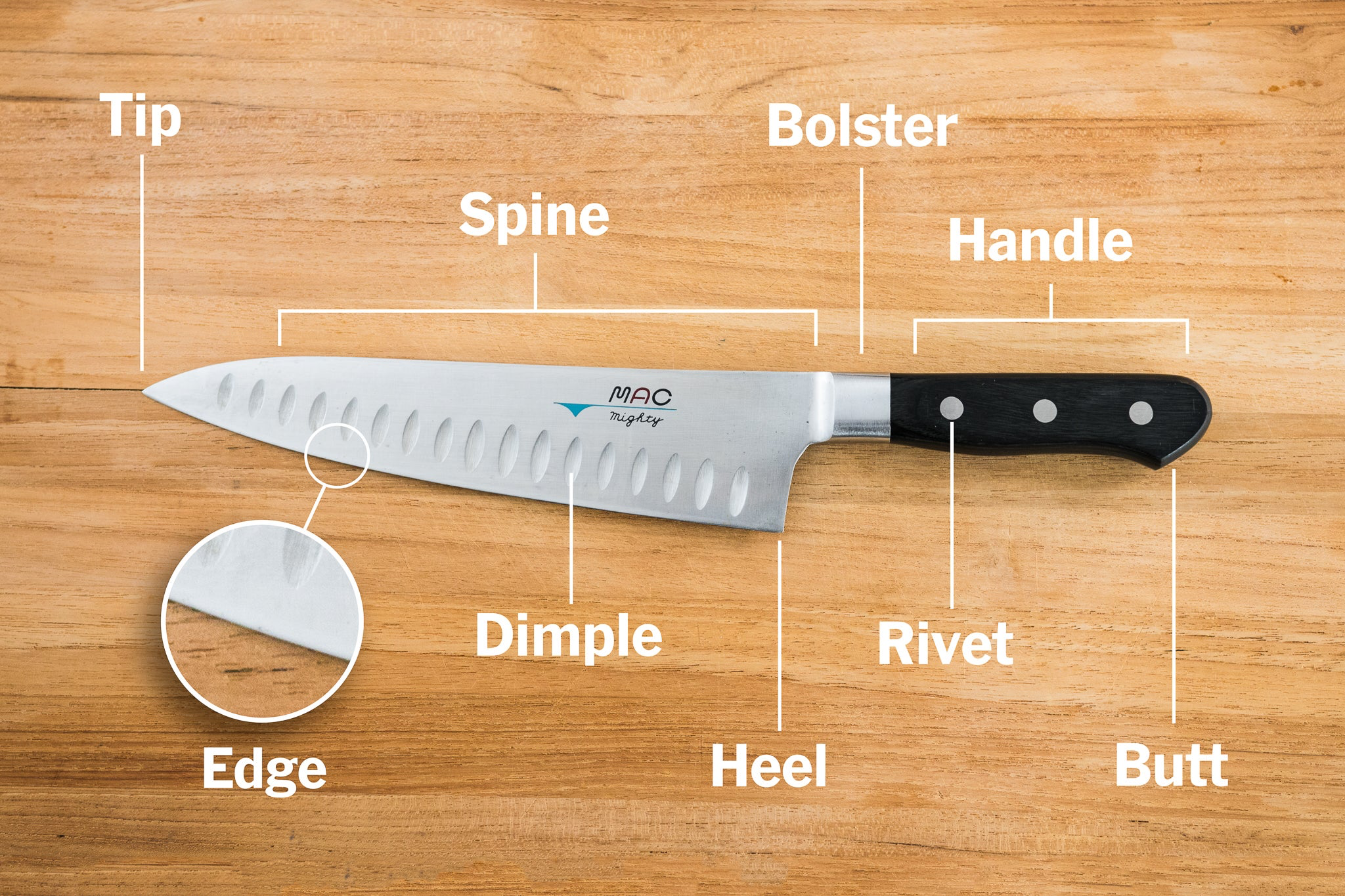

The Anatomy of a Kitchen Knife

Knowing your way around a knife is like knowing the controls on a car — once you understand what everything does, you drive smoother.

- Blade: The business end. Usually tapers from heel (back) to tip (front). The edge is what does the cutting. The spine is the top — it affects weight and balance.

- Point: The very tip — useful for piercing, detail work, or just starting a cut.

- Heel: The thick part of the blade near the handle — where you bring force when chopping something tough like squash or chicken bone.

- Bolster: That thick chunk of metal between blade and handle on some Western knives. Adds weight and balance, but also limits sharpening over time. Not every knife has one — and some folks prefer it that way.

- Tang: The part of the blade that runs into the handle. Full tang = more durability and better balance.

- Handle: Obvious, but underrated. The shape, material, and grip feel determine whether this knife becomes an extension of your hand — or something you dread picking up.

Western vs. Japanese Philosophy

Most home cooks don’t know they’re choosing between centuries-old traditions every time they pick up a knife. But they are.

- Western knives (think German or French brands like Wüsthof or Sabatier) are usually thicker, heavier, and designed for rocking cuts. They’re built to take abuse — bone, squash, frozen food, all fair game. They often have a bolster and full tang.

- Japanese knives (like Shun, Masamoto, or MAC) are usually thinner, harder, and sharper — but more brittle. Designed for precision slicing, not brute force. Less forgiving if you mistreat them, but rewarding if you don’t.

It’s not about better or worse. It’s about what fits your cooking style. Do you chop with muscle or glide with control? That’s the real fork in the road.

Steel: The Soul of the Blade

You can’t see what a knife’s made of while it’s sitting in your hand, but you’ll feel it after a week in your kitchen.

- Stainless Steel: Easy to maintain, resists rust, doesn’t need babying. But not all stainless is created equal — some cheap blades lose their edge in days. Look for high-carbon stainless if you want a middle ground between durability and sharpness.

- Carbon Steel: Razor-sharp, holds an edge forever — but rusts if you so much as breathe on it after slicing a lemon. Needs regular oiling and a little care. Think of it like cast iron: high maintenance, high reward.

- Powder Steel / SG2 / VG10 / fancy alloys: Mostly found in high-end Japanese knives. The metallurgy gets nerdy fast, but here’s the gist: they’re engineered for long edge retention and performance. If you’re sharpening your own blades and cooking every day, these are worth knowing.

- Ceramic: Stays sharp forever — until it chips or shatters. Light, brittle, and non-reactive (great for fruit and veggies). But once it’s dull, you can’t fix it at home. It’s a specialized tool, not a daily driver.

Grind, Bevel, and Edge Type

This is where sharpness lives — not just how sharp a knife is, but how it cuts.

- Double bevel: The standard edge type — sharpened on both sides. Most Western and many Japanese knives use this. Balanced, versatile.

- Single bevel: Only sharpened on one side, flat on the other. Used for ultra-precise Japanese knives like yanagiba or usuba. Not beginner-friendly, but unbeatable for paper-thin slices and beautiful presentation.

- Hollow grind: Creates a super thin edge — scary sharp, but more delicate.

- Convex grind: Slightly curved edge — stronger and more durable, but harder to sharpen yourself.

Most knife guides skip this stuff or bury it in jargon. But these basics — steel, shape, grind, philosophy — affect everything. Whether you’re slicing onions or deboning fish, they shape how the knife feels, how it moves, and whether it makes you feel like a kitchen ninja or a frustrated amateur.

Core Knife Types (And Why You Actually Need Them)

Let’s skip the bloated knife block with twelve mismatched blades and three that never get used. Most people — even serious home cooks — get 90% of their work done with two or three knives. But to know which ones matter for you, it helps to understand what each type is built to do, and what it feels like in your hand when it’s doing it right.

This section isn’t about owning every knife. It’s about knowing what they’re for.

Chef’s Knife

This is the workhorse. If you could only have one knife, this would be it. Usually between 8 and 10 inches long, with a broad, slightly curved blade that lets you rock it forward as you chop. The tip lets you do detail work, while the heel gives you power. Western chef’s knives tend to be thicker and more curved, built for volume and muscle. Japanese-style chef’s knives (Gyuto) are thinner, flatter, sharper, and more precise — designed for cleaner cuts and less resistance.

Use it for: slicing vegetables, cutting meat, mincing herbs, smashing garlic, everything.

Avoid using it for: cutting bone, hacking frozen food, or doing tasks better suited to something smaller.

If you’re only going to learn knife skills with one blade, this is the one. Everything else builds from here.

Santoku

Think of this as the chef’s knife’s sleeker cousin. Shorter, usually around 7 inches, with a flatter edge and a sheepsfoot-style tip. That shape makes it better for up-and-down chopping rather than rocking motions. It’s nimble, balanced, and great for people with smaller hands or tighter cutting spaces. The name means “three virtues” — slicing, dicing, and mincing — and that’s exactly what it’s good at.

Use it for: prepping vegetables, boneless meat, seafood, herbs, and everyday kitchen tasks.

Avoid using it for: heavy-duty work, big squash, or anything where you need a pointed tip.

If you like clean, straight cuts and a lighter feel in the hand, the santoku might edge out the chef’s knife for you.

Paring Knife

Small but essential. This is your go-to for anything that needs a delicate touch — peeling fruit, segmenting citrus, deveining shrimp, trimming fat, coring strawberries. Usually around 3 to 4 inches long, with a narrow blade you can steer with your fingertips. Not glamorous, but surprisingly crucial.

Use it for: detail work, handheld cutting, anything where a full-size blade feels clumsy.

Avoid using it for: anything that sits on a cutting board. It’s a precision tool, not a slicer.

A dull paring knife is useless. A sharp one feels like a scalpel in the best way.

Serrated (Bread) Knife

This one doesn’t get enough credit. Long blade, sawtooth edge, built to grip and slice without crushing. Ideal for bread, of course — especially crusty loaves — but also perfect for slicing tomatoes, citrus, cake layers, and anything soft-skinned with a soft interior.

Use it for: bread, baked goods, ripe fruit, sandwiches.

Avoid using it for: meats, dense vegetables, or precision cuts.

You don’t sharpen this often — the teeth do the work — but when it’s sharp, it feels almost unfair.

Utility Knife

Mid-sized and in search of a purpose. Sits between a paring knife and a chef’s knife, usually 5 to 6 inches long. Some people love them; others forget they exist. Good for sandwich prep, medium fruits and vegetables, and anything where you want control but don’t need a huge blade.

Use it for: trimming, slicing cheese, cutting through packaging or twine in a pinch.

Avoid using it for: anything a chef’s knife or paring knife can clearly do better.

It’s not essential — but once you find your rhythm with it, it can be a favorite.

Boning Knife

Narrow, slightly curved, and designed to follow muscle and bone. Comes in stiff or flexible versions. The flexible version hugs joints and glides along bones, perfect for poultry and fish. Stiffer ones are better for trimming fat and silver skin from red meat.

Use it for: deboning chicken, filleting fish, trimming beef.

Avoid using it for: cutting through bone — it’s meant to navigate, not break.

It’s sharp, precise, and potentially dangerous if you’re not confident — but if you handle a lot of raw meat, it’s a game-changer.

Fillet Knife

More specialized than a boning knife, and almost always flexible. Thin, with a long narrow blade that lets you slip under skin and separate delicate flesh with minimal damage. Mostly used for fish, but good for any kind of ultra-precise protein work.

Use it for: skinning fish, trimming fat, slicing thin pieces of raw meat.

Avoid using it for: anything heavy or dense — this knife is finesse-only.

A must-have if you break down your own fish. Otherwise, it’s optional.

Cleaver

There are two kinds here, and they couldn’t be more different.

- The Western-style cleaver is thick, heavy, and made for brute force — splitting bone, hacking through cartilage, breaking down ribs.

- The Chinese-style cleaver (cai dao) looks huge but is actually a delicate, precise tool. The blade is thin, straight, and incredibly versatile — used for slicing vegetables, smashing garlic, scooping ingredients, and yes, even cutting meat.

Use Western cleavers for: butchery, bone, impact cutting.

Use Chinese cleavers for: everything else. They’re shockingly precise, if you learn to trust the size.

Avoid using either for: delicate trimming work — they’re either too much or too awkward for fine detail.

Nakiri and Usuba

Both are Japanese vegetable knives, but they take slightly different routes.

- Nakiri: double-beveled, flat blade. Fast, rhythmic chopping. Great for home cooks.

- Usuba: single-beveled, more delicate, more specialized. Used in professional Japanese kitchens.

Use them for: precision vegetable work — shaving, slicing, chopping.

Avoid using them for: meat, bones, or rock-chopping. These want straight, clean movement.

If you do a lot of plant-based cooking, this kind of knife feels like an extension of your thought process.

Slicing and Carving Knives

Long, narrow blades built for clean, even slices — think roasts, brisket, turkey, ham. They glide through protein without tearing or sawing. Some have a granton (dimpled) edge to prevent sticking.

Use them for: roast carving, smoked meats, presentation slicing.

Avoid using them for: anything where control matters more than length. These are long and awkward unless the job calls for them.

This is the one you pull out a few times a year — and when you do, you’re glad you have it.

Specialty Knives

There are plenty — tomato knives, cheese knives, oyster shuckers, grapefruit knives, mezzalunas, and more. Most aren’t essential, but they serve a specific purpose well.

Use them for: exactly what they were made for.

Avoid using them for: everything else.

They’re like tools in a shed — fun if you know what you’re doing, unnecessary if you don’t.

Knife Sets vs. Buying Individual Blades

Walk into any kitchen store and you’ll see them — big, gleaming blocks of knives lined up like a military formation. Fifteen pieces, nineteen pieces, some with shears and sharpeners and steak knives thrown in. A few of them are decent. Most are a waste of money and drawer space.

The idea behind a knife set is convenience. One purchase, and you’re covered. But here’s the problem: most sets include knives you’ll never use and skip the ones you’ll eventually want. They look complete — but they’re usually built around filler.

What You Get in a Typical Set

Here’s what most standard sets include:

- 8″ chef’s knife (usually the best blade in the bunch)

- Bread knife

- Utility knife

- Paring knife

- A few steak knives (not useful for prep)

- Kitchen shears (sometimes decent)

- Honing steel (often too soft to do anything)

- A “block” that takes up half your counter

That sounds comprehensive until you realize none of these knives are great — just passable. The chef’s knife might work for a while, but the steel’s usually soft, the edge retention is poor, and after six months, it’s dull and chippy. The others are often carbon copies of each other in different sizes.

Sets are built to impress at the moment of sale, not to last in the kitchen.

Why Buying Individual Knives Is Smarter

When you buy knives one by one, you build a kit that reflects how you actually cook. You spend more where it counts (chef’s knife, santoku, paring), and skip the stuff you’ll never reach for. You also get to choose steel quality, handle shape, blade geometry — things that directly affect comfort and performance.

It’s also easier to upgrade. One great knife now. Another next year. And nothing in your drawer is dead weight.

Start with one solid all-purpose knife. Learn it. Maintain it. Then build around it based on gaps you actually notice — not ones a marketing team tells you you’ll have.

When a Set Might Make Sense

There are exceptions. If you:

- Cook for a large household and need multiple hands working at once

- Want matching knives for a shared kitchen setup

- Are buying for a beginner who genuinely doesn’t know where to start

- Find a high-end set with no filler (rare, but possible)

…then a set can be a good starting point. But treat it as a temporary scaffold, not a permanent solution. You’ll likely outgrow half of it.

Red Flags to Watch For in Knife Sets

- Too many knives under $100 — corners were cut, probably at the steel.

- Anything with “never needs sharpening” on the box — false promise.

- Hollow handles — lightweight, often unbalanced, and uncomfortable for real prep work.

- Oversized blocks — more about visual presence than function.

There’s nothing wrong with buying multiple knives at once. Just make sure you’re not paying for foam packed in steel.

Care, Storage, and Maintenance

You can spend $30 or $300 on a knife, but if you treat it wrong, it’ll end up dull, chipped, and sad all the same. Good knives don’t need pampering, but they do need respect — and most of that comes down to three things: how you store them, how you clean them, and how you maintain the edge.

Honing vs. Sharpening

This gets confused constantly.

- Honing is what you do regularly. It realigns the microscopic edge of the blade. You’re not removing metal — just straightening out the burrs that bend with use. Think of it like brushing your teeth.

- Sharpening is what you do when honing no longer helps. It actually grinds away material to create a new edge. This is surgery, not grooming.

A honing rod (steel or ceramic) keeps your edge in shape between sharpenings. Done right, it extends the life of the blade. Done wrong — or skipped entirely — your knife dulls faster and sharpens worse.

Rule of thumb: hone every few uses, sharpen every few months (or when you notice slippage on tomatoes and onions).

Cutting Boards Matter More Than You Think

Wood or plastic. That’s it. End of list.

Glass, marble, ceramic — they destroy knife edges. Instantly. Those boards aren’t for cutting. They’re for serving cheese to people you don’t like.

Softwood (like hinoki or rubberized composites) is gentler on blades. Hardwood (like maple or walnut) is durable and stable. Plastic boards are fine too — just keep them clean and replace them once they get deeply scored. Bacteria loves those grooves.

Never cut directly on a plate, tray, or countertop. You’ll feel cool for a second, then regret it when your blade feels like a butter knife the next day.

Storage: How to Keep Knives Sharp and Your Fingers Intact

There’s no single best method — but there are a few safe ones.

- Magnetic strips: Great if you have wall space. Keeps edges dry, separated, and accessible. Just avoid slapping them on sideways — that’s how chips happen.

- In-drawer knife trays: Keeps blades protected and off the counter. Ideal if you want a clean look. Just don’t let them rattle loose in a junk drawer.

- Knife blocks: Fine, but only if they fit your knives snugly. Loose slots dull blades. Vertical blocks collect crumbs and moisture — go for angled or side-loading if possible.

- Blade guards (sheaths): Cheap, simple, especially good for travel or shared kitchens. Protects the knife and your hands.

What not to do: toss your knife into a drawer full of utensils and forget about it. That’s how tips break and edges dull, fast.

Cleaning: No, You Can’t Use the Dishwasher

Even if the packaging says “dishwasher safe,” ignore it. That’s legal language — not kitchen logic.

Dishwashers rattle knives around, heat them unevenly, and expose them to detergent that corrodes steel over time. Handles crack, edges dull, and tips get bent or banged up.

Hand wash with warm water, mild soap, and a soft sponge. Dry immediately. That’s the whole routine. Takes 20 seconds, and your knife lasts years longer.

When and How to Sharpen

If you’re comfortable, learn to sharpen on a whetstone. It takes practice — and patience — but it gives you full control. Plus, it’s satisfying in the way that mowing a perfect line into overgrown grass is satisfying.

If you’re not ready, take it to a pro. Not the grocery store guy with the belt sander. Look for someone who works with chefs or Japanese knives. It might cost $5–10 per knife, but a clean edge once every few months is worth every cent.

Avoid pull-through sharpeners unless you’ve got a $20 knife you don’t care about. They strip metal fast and give you an edge that looks sharp, but folds within a week.

Bottom line: knives don’t need pampering. They need routine, a clean surface, and the occasional tune-up. Treat them like kitchen tools, not collectibles — but don’t treat them like hammers either.

How It Feels in the Hand: Balance, Weight, and Fit

You can memorize steel types, blade geometry, and brand names all day — but none of it matters if the knife feels wrong in your hand. Comfort isn’t a bonus. It’s the whole game. A knife that fits you moves better, cuts easier, and wears you out less. And oddly enough, you usually know it within seconds of picking it up.

Weight: Light vs. Heavy

There’s no right answer — just personal preference and task alignment.

- Lighter knives (like most Japanese blades) feel agile, faster, and more responsive. You do the work; the knife follows. Great for slicing, vegetables, finesse cuts.

- Heavier knives (like German or French chef’s knives) let gravity help. You guide the blade, and it falls through food on its own. Great for dense ingredients, long prep sessions, or people who like to feel the tool’s presence in their hand.

A heavy knife might seem powerful at first, but if it tires your wrist after ten minutes, it’s a mismatch. Light knives can feel surgical — until you try to break down a squash and wish you had backup.

Balance: Forward, Neutral, or Handle-Heavy

Balance affects how the knife moves through food and how much energy you use to steer it.

- Blade-heavy knives tend to swing forward, good for power cuts but harder to control.

- Handle-heavy knives feel clunky and awkward — like driving a pickup with bricks in the bed and no front tires.

- Neutral balance — typically right at the bolster or heel — is the sweet spot for most people. The knife feels like a natural extension of your arm, and it moves without resistance.

You won’t get this from pictures. You need to hold it. Better yet, use it.

Handle Shape and Size

Even good blades can feel wrong if the handle’s not built for you.

- Western handles are usually rounded or contoured, meant to fill the palm. Comfortable, familiar, grippy.

- Japanese handles (wa handles) are often lighter, more angular, and positioned further forward for precision. Great for control, but less forgiving if you’re not used to the feel.

- Octagonal or D-shaped handles provide tactile feedback — you always know where the edge is. But they can feel odd if you’re used to symmetrical grips.

Try them all if you can. Some feel like tools. Others feel like home.

Materials: Wood, Plastic, Resin, Composite

- Wood looks great, feels warm, and grips well — but needs care. No soaking, no dishwasher.

- Plastic or synthetic handles are easy to clean, low maintenance, and cheap — but can feel slick or generic.

- Resin-stabilized wood gives you the best of both — beauty and durability.

- Micarta, G10, Pakkawood, composite materials — used in better knives. Durable, balanced, textured. Often a sweet spot between performance and resilience.

Materials matter most when wet. If a handle gets slippery, sticky, or gummy mid-prep, you’ll stop trusting it.

Fit: The Knife Isn’t Supposed to Hurt You

If a knife digs into your palm, slips around, or makes your wrist ache — it’s not your knife. Doesn’t matter how well it scores on Reddit. It’s not a contest. It’s an extension of your body.

Test it with your standard grip. If your hand has to adjust to the knife instead of the other way around, walk away.

A good knife disappears when you use it. You don’t think about weight or balance or the shape of the grip. You just slice, chop, move, and breathe. That’s how you know it’s right.

Choosing Your First Real Knife: A Field Guide

You don’t need to be a chef to own a great knife. You just need to be someone who cooks regularly and wants to stop fighting their tools. This isn’t about buying the “best” knife on the market — it’s about buying one that actually fits you. Your grip, your food habits, your kitchen routine.

Here’s how to approach it when you’re ready to graduate from the dull mystery steel living in your drawer.

Start With One Knife That Does Most of the Work

For most people, that’s an 8″ chef’s knife or a 7″ santoku. If you’re comfortable with a rocking motion and often prep large amounts of food, go chef’s knife. If you prefer clean, straight slices and a more compact feel, try a santoku.

You don’t need a full set. One solid, versatile knife that stays sharp and fits your hand will outcook ten dull ones every day of the week.

Go Somewhere You Can Hold It (If You Can)

Pictures don’t show balance. You can’t feel weight distribution through specs. A knife that looks perfect online might feel clumsy or tip-heavy in person. Go to a kitchen store if there’s one near you. Grip a few different styles — German, Japanese, hybrid. See what feels natural.

Pay attention to:

- Where your fingers land

- Whether the handle fits your palm

- If the tip feels like it’s dragging or floating

If it disappears in your hand when you hold it, that’s a good sign.

Shopping Online? Read Between the Lines

If in-person testing isn’t an option, online reviews help — but you have to know what to look for.

Red flags:

- “It’s sharp out of the box” — so are steak knives at a diner. The question is, does it stay sharp?

- “Doesn’t rust even in the dishwasher” — no good knife should ever go in the dishwasher

- “Feels sturdy” — vague praise often means it’s clunky

Green flags:

- Users talk about edge retention over months, not days

- Reviews mention sharpening response (some steels resist home sharpening)

- The maker discloses the steel type — if they hide it, it’s cheap

Brands With Credibility

You don’t need to buy the most expensive brand. But avoid total unknowns that promise too much for too little. Here’s a loose lay of the land — not endorsements, just recognition.

- Reliable western makers: Victorinox, Wüsthof, Messermeister, MAC, Sabatier

- Affordable Japanese-style options: Tojiro, Misono, Global, Shibata

- Boutique/high-end: Takeda, Masakage, Konosuke, Kato, Ashi Hamono

Some Japanese makers use house branding, so not everything will show up on Amazon. Specialty knife shops or importers are your friend.

Don’t Buy Above Your Skill Level

There are knives out there so sharp and delicate, they’ll chip if you tap them wrong. There are also blades so thin they’re miserable if you don’t cut with perfect technique.

If you’re still learning, get something forgiving. High-carbon stainless is a great balance. Go too hard, and you’ll end up babying the knife instead of using it.

Price Range That Makes Sense

- $50–100: Solid starter territory. Look for forged steel, not stamped. Japanese or German styles, maybe a resin or plastic handle.

- $100–200: Where real performance starts. Better edge retention, more comfortable shapes, finer grinds. Still approachable.

- $200–400: Specialty blades. Hand-forged, artisanal steels, tailored balance. Worth it if you cook a lot or just love beautiful tools.

- $500+: You’re either a collector, a chef, or you’ve decided to make this your thing. No judgment. Just know what you’re getting into.

The sweet spot for most home cooks is in the $80–150 range — enough quality to last, not so much you’re afraid to use it.

A real knife changes how you move in the kitchen. It doesn’t just slice better — it makes prep feel smoother, faster, more intentional. You find yourself cooking more often, chopping more confidently, and caring more about the rhythm of the process.Frequently Asked Questions

You’ve got your blade. You’ve figured out how to hold it, store it, sharpen it. But the same questions come up again and again — online, in kitchens, at knife shops, even at dinner parties if the wine’s good. So let’s knock them out, one by one.

Frequently Asked Questions

You’ve got your blade. You’ve figured out how to hold it, store it, sharpen it. But the same questions come up again and again — online, in kitchens, at knife shops, even at dinner parties if the wine’s good. So let’s knock them out, one by one.

How often should I sharpen my knife?

It depends on how much you use it and what you’re cutting. For a home cook using their main knife most days of the week? Two or three times a year. You should be honing regularly — that keeps the edge aligned — but sharpening is about restoring what’s lost.

If you notice your knife slipping on tomatoes, smashing herbs instead of slicing, or skidding off onion skins, it’s time.

Why does my knife go dull so fast?

Usually one of three things:

- You’re using a bad cutting surface (glass, granite, ceramic — all edge killers).

- You’re storing it loose in a drawer.

- You’re not honing it between uses, so the edge deforms and dulls faster.

Also worth noting: softer steels dull faster but sharpen easier. Harder steels stay sharper longer but chip if mistreated. Know what you’re working with.

Is Damascus steel worth it?

Damascus refers to the pattern — the result of layered or etched steel — not necessarily the performance. Some Damascus blades are excellent. Some are cosmetic garbage. Don’t buy a knife because it looks wavy. Buy it because it cuts well, holds its edge, and fits your hand. The pretty stuff is bonus.

What’s the best all-purpose knife for a small kitchen?

A 7–8″ chef’s knife or santoku, depending on your style. Gyuto if you want something light and Japanese. MAC or Victorinox if you want good steel on a budget. You don’t need a drawer full — just one you trust.

Are ceramic knives a scam or underrated?

Neither. They’re specialized. Ceramic blades stay sharp for a long time and don’t rust — great for fruit, vegetables, boneless proteins. But they’re brittle. Drop one and it might shatter. Try to cut a bone or twist mid-cut, and you’ll chip it.

Use them if you want low-maintenance slicing. Avoid them if you want a daily driver.

Can I use one knife for everything?

Technically yes — people do it every day. A good chef’s knife or santoku can handle 90% of kitchen tasks. But using a big blade for paring work, or slicing bread with a smooth edge, makes life harder.

One knife can do everything. Two or three can do everything well.

What’s the most dangerous knife in the kitchen?

The dull one. Dull knives slip. They bounce. They force you to apply more pressure than you should, and that’s when fingers get in the way.

A sharp knife is predictable. It does what you tell it to. Keep it that way.

Should I oil my knives?

If it’s carbon steel, yes — after cleaning and drying, wipe a drop of food-safe mineral oil over the blade. It keeps rust away and prevents oxidation. If it’s stainless steel, you don’t need to — but it won’t hurt.

Never use cooking oil. It gets sticky and rancid over time.

What’s the deal with knife laws and carrying them for work?

Varies by country, state, and city. Some places allow chefs to carry knives for work purposes if they’re stored correctly. Others consider any concealed blade illegal regardless of context.

General rule: transport knives in a roll or case, not loose in a bag. And don’t assume good intentions will get you off the hook — check the law before you travel with tools.

That’s it. If your question wasn’t answered here, chances are it’s either super niche — or it boils down to: use the knife, pay attention to it, and don’t overcomplicate things.

Closing: The Knife You’ll Actually Use

The best knife in your kitchen isn’t the most expensive one, or the one with the prettiest pattern welded into the steel. It’s the one that’s always clean, sharp, and within reach when you start cooking. The one that moves the way your hand wants to move. The one you don’t have to think about because it’s just there — doing its job, every time.

Some people get obsessive about their knives. That’s fine. There’s plenty to love about the craftsmanship, the metallurgy, the edge geometry. But you don’t need to memorize any of that to make good food. You just need a tool that stays out of your way.

If this guide did its job, you now know how to find one. How to care for it. How to use it with a little more confidence. And maybe — just maybe — how to enjoy the process of cutting again.

Because whether you’re dicing onions at 6 p.m. with a kid pulling on your leg, or standing alone at the counter slicing a tomato so clean it doesn’t even notice, a good knife changes the way you cook. Quietly. Permanently.

And you’ll wonder how you ever put up with anything less.